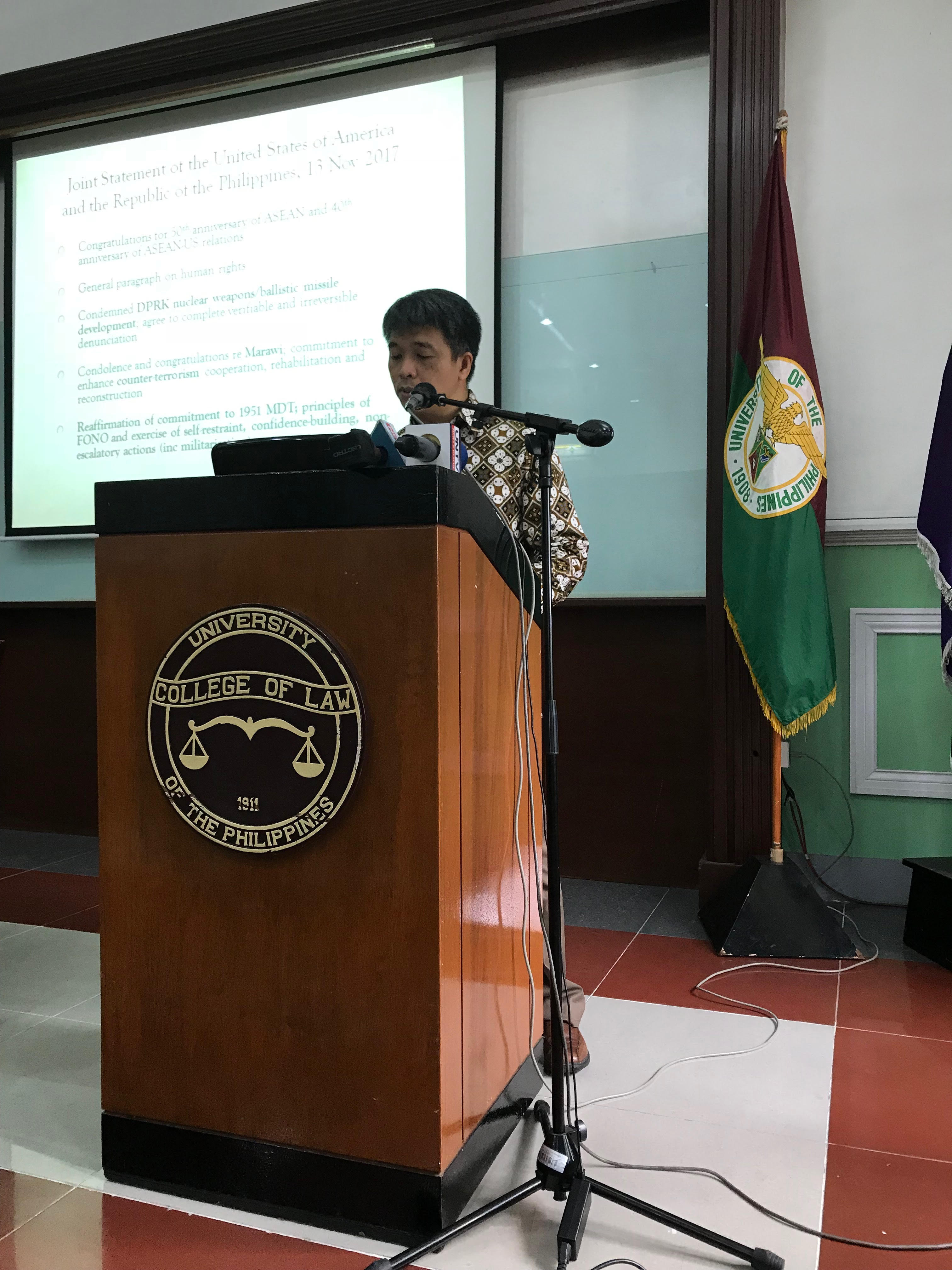

By: Dr. Jay L. Batongbacal, 13 May 2017

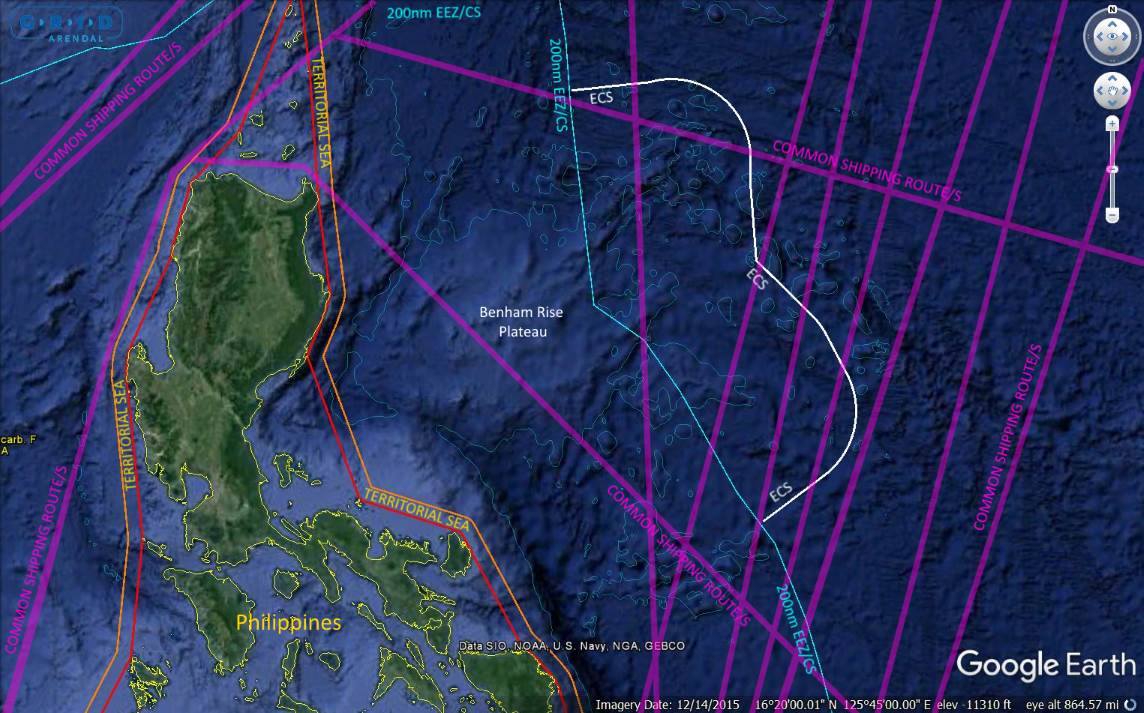

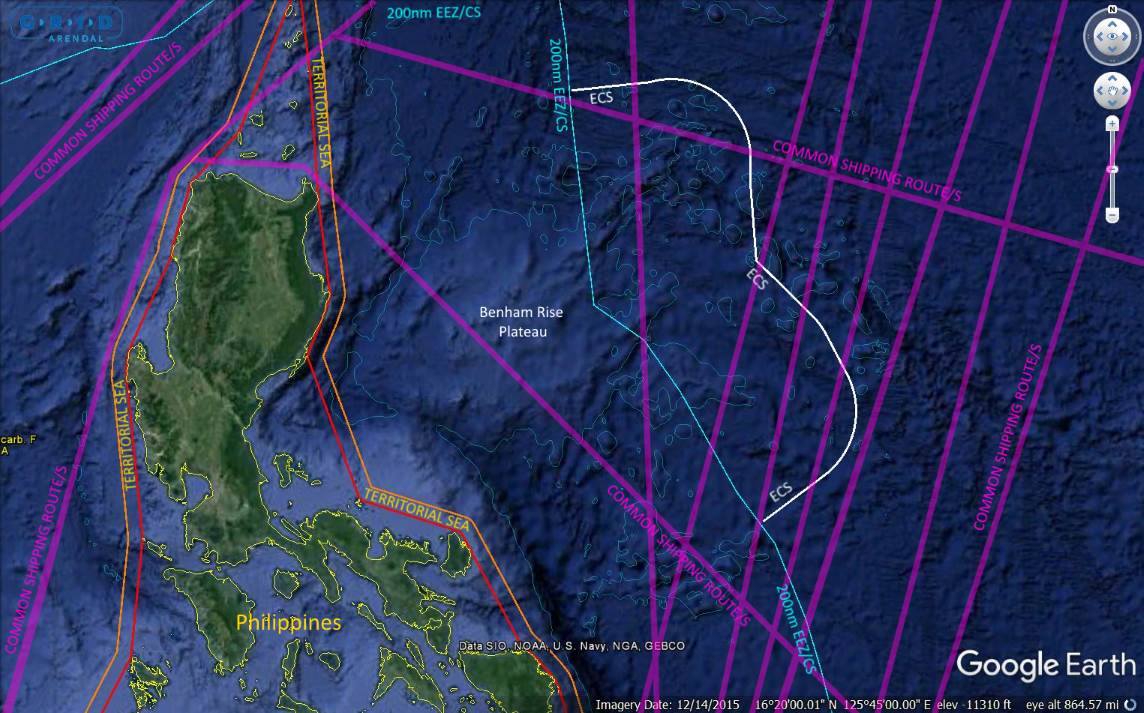

Benham Rise is an underwater plateau that stretches from the coast of Cagayan and Bicol up to approximately 300-350 nautical miles (nm) in the Pacific Ocean. A large part of this plateau is within the 200 nm Exclusive Economic Zone and continental shelf of the Philippines. An additional area of seabed extending around 150 nm was successfully claimed by the Philippines as its “extended continental shelf” (ECS) in accordance with Article 76 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. The region may not be “territory” in the same sense as land territory, but it is definitely “territory” for the purposes of Philippine laws and regulations over natural resources. The 1987 Constitution considers as legally part of the National Territory all areas over which the Philippines has sovereignty or jurisdiction; Benham Rise falls squarely within this definition.

Within 200 nm, the Philippines has exclusive sovereign rights to explore for, and exploit, living and non-living natural resources of both the water column (the EEZ) and the seabed beneath (the continental shelf). “Sovereign rights” may not be the same as full “sovereignty”, and people usually confuse these two terms. It is like confusing a person’s rights over property he holds under lease and rights to property he holds as a full owner. But the fact that the former is of a different status than the other does not make them any less enforceable under law.

These waters are subject to high seas freedoms available to all nations (including freedom of navigation and overflight), but such freedoms must be exercised in a way that respects, and gives due regard to, the sovereign rights of the Philippines. In addition, the Philippines has the right to regulate and participate in any marine scientific research (MSR) conducted in this area.

Beyond 200 nm, but within the area of the ECS, the water column is considered to be part of the high seas subject to the common rights and freedoms of all States. But the seabed underneath is still subject to the exclusive sovereign rights of the Philippines for purposes of exploration and exploitation of seabed resources. No other State may carry out activities for these purposes in the seabed in this area, even though they may exercise rights and freedoms on the waters above it. This is the area that was recognized by the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) to be the Philippines’ ECS.

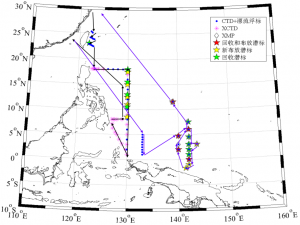

The reported activities of China therefore have to be viewed with an eye for careful legal nuances. SND Lorenzana described Chinese survey vessels to have been passing through, or to have been stationary for extended periods of time, or moving in a criss-cross/back-and-forth pattern. Naturally he cannot describe in detail what these vessels were doing, he can only see how the vessels are moving. But that is enough to make some reasonable assumptions. Even without direct visual sighting, the movement of a ship (such as that recorded on a radar plot, or by satellite) tells a lot about its activities.

The first point is this: a vessel is merely passing through if it is moving at a steady pace in one direction, obviously travelling from a distinct place of origin to a specific destination. UNCLOS Part II guarantees the right of foreign vessels to pass through the waters of coastal States subject to certain rules. If it is moving through territorial waters (i.e., within 12 nm from shore) its right to do so is guaranteed by the “right of innocent passage.” Beyond territorial waters, i.e., in the EEZ and high seas, it does so in exercise of “freedom of navigation,” likewise guaranteed by UNCLOS, but such freedom of navigation, by its very name, refers only to the act of navigating on water. It does not connote freedom to undertake any other activity. Such other activities will be governed by the rules applicable to either the EEZ or the high seas, wherever the ship may be located at the time.

This takes us to the second point: within the EEZ of a coastal State, a ship exercising freedom of navigation must respect the exclusive sovereign rights of the coastal State to its EEZ and continental shelf. These rights of a coastal State include regulatory jurisdiction over activities which have the purpose of exploring and exploiting the living and non-living resources of the water column and the seabed within 200 nm from shore. These are guaranteed by UNCLOS Part V and VI. They also include regulatory jurisdiction over activities that fall within the purview of “marine scientific research.” This is governed by UNCLOS Part XIII. While the extent of coastal State jurisdiction varies, they all require the basic element of coastal State consent.

A ship may be assumed to be doing more than exercising freedom of navigation if it is moving in a way that is not in accord with the general objective of navigation: to get from one place to another. If, for example, a ship becomes stationary for a long period of time in one place, either keeping in one specific spot or drifting somewhat, before again moving purposely, or doing so repeatedly, it is reasonable to assume that it is not merely navigating. It is likely doing something else, such as taking soundings, dropping probes, deploying divers or remotely-operated vehicles, or some other activity that requires the ship to stop navigating.

If a ship moves in a direction that is not a straight line, it does so not merely to navigate, but in connection with another activity entirely. If it is moving in circular, zigzagging, or other irregular patterns, it is reasonable to assume that it is chasing fish (or some other object), or actually fishing (or something similar), or doing something else entirely (like military exercises). If it is moving in a regular criss-crossing or back-and-forth pattern at regular intervals, it is likely mapping the ocean floor with sonar or other device. All of these activities indicate that the ship is not merely passing through (i.e., exercising either the right of innocent passage or the freedom of navigation) but is actually doing something else: either marine scientific research, or military activities such as exercises or hydrographic/oceanographic surveys. It becomes even more probable if the ship either returns to its port of origin, or goes to another place that it could have gotten to very easily and in far less time had it not carried out its various movements.

Bringing the situation back to Benham Rise, see the graphic provided.

Continue reading →