By: Dr. Jay L. Batongbacal

China has openly identified marine science and technology through the conduct of marine scientific research (MSR) as vital for the development of maritime power, and has laid out a roadmap to 2050 outlining the means and methods for doing so. To this end, it has invested heavily in its academic and research institutions, fully modernized and upgraded its MSR vessels into the largest and best in the world, and embarked on national and international ocean research programs. It has 46 vessels already in operation, with more being built and pressed into service. The most modern ship, the Xiang Yang Hong 01, is a globally-mobile ocean laboratory capable of long-range voyages and deep-sea research, and if necessary can be operated by one person on the bridge.

Alarm over the grant of consent for conduct of MSR by the Institute of Oceanology of the China Academy of Science, subject to the condition that it partner with the University of the Philippines’ Marine Science Institute, is perfectly understandable given China’s spotty record in demonstrating respect for Philippine jurisdictions and its expansive maritime claims in the West Philippine Sea. Since 2016, a marked increase in MSR activities in the WPS have raised suspicions that China is deploying these vessels as a “grey zone tactic” to assert and demonstrate jurisdiction and administration of its claimed waters.

The PRRD Administration’s quiescence in the face of this increased activity, which included surveys and use of submersibles in areas around the Kalayaan Islands, Scarborough Shoal, and Reed Bank has done nothing to assure Filipinos of the government’s insistence that it continues to protect its maritime interests. International law does not sanction (and even expressly proscribes) the use of MSR activities as a means of asserting and proving sovereignty and jurisdiction over maritime space. But this has not prevented suspicion over China’s objectives, hence, even more intense suspicions were raised once Chinese MSR activities began intensifying on the Pacific seaboard as well.

Last year, the security sector’s suspicions over the recorded presence of another MSR vessel (the Xiang Yang Hong 03) in the vicinity of Benham Rise found an outlet and resonated with the broader public, signaling their dissatisfaction with the administration turning a blind eye to China’s activities. China was constrained to expressly recognize Philippine jurisdiction over Benham Rise and profess that it was merely passing through the area in order to carry out legitimate research activities. But as I noted back then, it would not be the last time for Chinese MSR vessels to be present in that region. In fact, Philippines should expect such voyages to continue well into 2019, and most likely beyond even that.

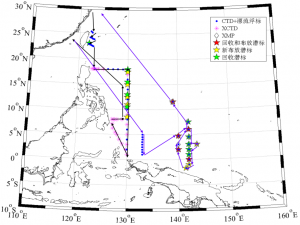

The reason for this is that China is conducting two major ocean science programs: the Northwestern Pacific Ocean Circulation and Climate Experiment (NPOCE) and the Western Pacific Ocean Systems (WPOS) Project. As early as 2012, Chinese MSR vessels have been studying the Pacific ocean currents which happen to flow towards Mindanao, particularly near Surigao, as part of the NPOCE, an international research program involving not only China but also the US, Japan, Korea, Australia, and Indonesia. In 2014, China embarked on its own with the WPOS, its single largest investment in national ocean sciences through intensive studies of the seabed and oceans. The study areas cover the high seas of the Pacific but also extend into the eastern Philippine EEZ, since they follow ocean currents until they collide with and divert from the narrow continental margins of the country.

Under UNCLOS, coastal States are entitled to regulate MSR conducted by foreign vessels within their EEZs. To strike a balance between the need for security of coastal State interests in their natural resources with the general public interest in conducting MSR, UNCLOS requires researching States to secure the consent of coastal States if the research will be conducted in the EEZ of the latter. Coastal States are encouraged to timely grant such consent, subject to the requirement that the researching State should allow the coastal State to participate in the MSR, and share data and information acquired. Coastal States normally cannot refuse such consent, unless the research has implications for natural resource exploration and exploitation, involves drilling and introduction of harmful substances into the marine environment, construction or installation of artificial islands or facilities, or if the researching State did not provide accurate information to secure consent, or has outstanding obligations to the coastal State with respect to MSR previously undertaken. A coastal State has to make a decision on a request for MSR; if it does not disapprove a request on appropriate grounds within 4 months from receipt, it is deemed to have impliedly granted consent. MSR should be conducted for exclusively peaceful purposes and should redound to the public good. Studies of ocean currents like the NPOCE and WPOS, for example, have very important applications for monitoring and anticipating weather events and climate change.

The Philippines has world-class marine scientists; people in UP-MSI, UP-Visayas, Silliman University, and other institutions have been educated and trained in the same institutions abroad as many Chinese scientists, and they are part of a global community of academics who are familiar with each other’s work and institutions. But there are still so few of them, and they have little equipment to work with. Despite our archipelagic status, the Philippines has invested too little in its marine science capacities and capabilities; it can barely mount its own occasional expeditions in Benham Rise, much less participate in international research programs and projects that are conducted every year by most advanced nations in the oceans around us. If the country is to improve its capacities and capabilities in this regard, then it must engage in scientific cooperation with other States whenever the opportunity arises. Right now and into the foreseeable future, Chinese MSR represents huge opportunities.

These opportunities are not without risks: while MSR can produce public goods, such goods can be value-neutral and also have resource and military/strategic applications. China’s record in creative interpretation, dual-use, revisionism, and “retroactive continuity” to gain advantages over its partners and neighbors is also a constant reminder of need to maintain a healthy skepticism and reason enough for suspicion over its motives and objectives. As with any endeavor, these have to be weighed against the potential advantages that the country might get from cooperation and participation in massive MSR programs.

One thing is certain: non-participation and disapproval without enforcement is not acceptable. These MSR programs will continue to be conducted, and the knowledge and information they generate will continue to be needed and used by the country. It gains nothing and loses a lot from not accessing the research opportunities and outputs; it even prevents itself from carrying out effective protective measures against mis-used MSR (since it won’t even know what the researching State is doing). Scientific isolationism in this regard will only hobble, not improve, its ability to govern its marine spaces. It would be just as bad as carelessly allowing everyone else to conduct MSR, effectively giving up its rights and jurisdictions over those activities.

The challenge is squarely laid before the Philippines: if it is serious about asserting its UNCLOS jurisdictions, it should be actively taking these opportunities and devoting people and resources to ensure that it can pursue and protect its interests. China, as well as other countries, will definitely gain advantages over us in knowledge of ocean processes and resources in the Pacific if we allow them to do so by not pro-actively engaging and participating in MSR, when the opportunity for such is both required by international law and actually made available.

There is an urgent need to review our past experiences and processes in dealing with foreign MSR in and around our waters, identify its shortcomings, and prepare to respond to what is now going on and what lies ahead. There is a need for government to open the record on these activities, inform the people of what has been taking place and what actions it has taken (or not) to protect Philippine interests, and whether they have been successful or counter-productive. Allowing foreign MSR is not a simple foreign policy prerogative, it is also an activity with potential advantages and disadvantages that can only be appreciated with proper and relevant expertise.

The Philippines indeed needs to hold China accountable for past transgressions in this regard, and it is proper to question the wisdom of allowing MSR in light of past experience in the West Philippine Sea and cherry-picking with UNCLOS. But, the Philippines must also must address continuing and future MSR activities. It is not enough to look into formal compliance with the legal processes under UNCLOS for securing consent; the country must also actively invest in, participate, influence, and extract tangible benefits from the MSR activities that increasingly take place around it. Fore-warned is fore-armed only if the Philippines actually does something about it. If not, then it will indeed be left behind, lost at sea.